A Book Review by Kartar Diamond

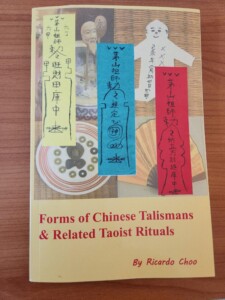

This self-published book was written by a man who studied formally with a talismanic academy called the Mao Shan Hua Yang Qing Feng Sect. That is a mouthful, but just one of many talismanic orders with its own distinct lineage and protocols.

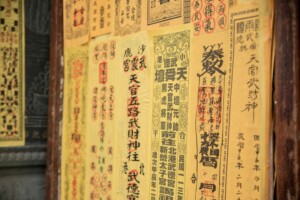

Choo shares interesting historical details of this mysterious Taoist practice and clearly explains why they are used, how they are used and the mechanics of creating a talisman. Specifically, the Chinese paper talisman is called a “fu.” As old as the practice of Feng Shui, Fu Talisman-making has been documented for at least several thousand years, with rivaling sects.

Choo writes, “The symbols in the Chinese Talisman are said to be that of symbols of the universe and allow the user/wearer to be in line with the natural forces, thus manifesting their wishes or assist them in their daily routines.”

He defines two basic types of talisman as “clear strokes” or “messy strokes,” which may be the difference between traditional sigils with beautiful-looking calligraphy in contrast with the “glyphs” which may look like “illegible” scribbles.

The different Talisman sects (or schools) gained recognition and loyal followings for having special skills or supernatural capabilities, infused in their fu-making. It brought a smile to my face to learn about the San Nai Sub-Sect where three ladies are referred to as “grannies” and people pray to them for safe childbirth or to look out for their children until they reach puberty. Truly an example that this esoteric practice can address any facet of mundane and supernatural life.

Special tools are used in making the fu. The author explains the process of “consecrating” those tools used and we learn fun facts, such as the specialness of seals carved out of wood that was struck by lightning. While describing the different types of ink used, we learn about one sect that uses the blood of a rooster, taken from the very top of its head, presumably without having to kill it. Mixing the blood or ink with rainwater was also deemed superior to other sources of water. Mixing the ashes in both cold and warm water can infuse the Talisman’s essence with both yin and yang powers.

A series of special protocols further inject the fu with more potency; this can include rituals done in certain directions, such as starting out facing east to capture the energy of spring-time. He describes four auspicious times of day to craft a fu, paying homage to the dimension of time and accessing the mixture of timely energies.

Between 11:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. is the cross-over time between one day and the next. Between 5:00- 7:00 a.m. is the time between night and dawn. Between 11:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. is the cross-over between morning and afternoon when the Qi is strongest. And then between 5:00 to 7:00 p.m. is between daylight and sunset.

Activating a fu, after it has been crafted and charged (infused with mantra), can include folding it into a triangular or octagonal shape, resembling Origami. Fu can be burned and the ashes used in a variety of ways. One way is to consume them and Choo explains how this became a common practice as a stand-in for unavailable medical treatment.

The numerous Talisman training sects are described like spiritual orders or competing mystical martial art schools. With religious overtones, initiates from certain sects must adhere to specific dietary regimes, such as not eating beef or not engaging in sex for a defined time frame before making the fu. While it may seem like an endless amount of protocols, I prefer to see them as “layers,” which make the fu that much more powerful and effective.

In Chapter 7, Choo explains that talisman (plural) can be combined with folk rituals and shares some surprising practices and extremely specific Fu, such as one done to “dissolve” fish bones stuck in the throat. It can even be done remotely on the person’s behalf. Of course, these practices predate use of phones or texting, so one wonders just how quickly a choking person can get in touch with their local Fu master. Another Fu is described for its power to soothe a crying baby and Fu can also be made to assist a person in shock, inability to focus or sleep. He relays a story about Taiwanese priests offering free talisman for those suffering from trauma after an earthquake in the year 921.

Choo explains a Taoist belief that the soul has 7 parts to it (related to different emotions) and 3 segments. People can experience a variety of ailments and mental disturbances when part of their soul has gone missing. The author mentions Fu that can be made to bring a married couple closer together and notes that images of a man and woman drawn on a Fu should have the male on the left and female on the right. This extends to other protocols, such as positioning protective stone lions outside an entrance. This is an example of the overlap between Taoist practice and Feng Shui remedies.

The correct placement follows suit with the male lion on the left and the female lioness on the right when looking toward the entrance. This actually mimics the correct depiction of the Tai Chi (Yin-Yang) symbol, where we should see the white (masculine side) on the left and the black (feminine side) on the right.

When using the reference point of “left” or “right,” I have read many instances where it still needs to be clarified whether one is looking toward or away from an object. In the case of Feng Shui, with the “sitting” or back side defining the house orientation, one needs to look at the Yin Yang symbol as one is standing facing the back of the house and looking at the symbol as if seeing through it.

Some Fu are done over several days, such as with a “Missing Persons” Fu, and some are also done for a period of time after the problem has been solved, as he describes it similar to taking an antibiotic for its full dose until the prescription runs out.

Choo also retells some wild stories, such as one from Malaysia where Fu were put in place to protect a home, to prevent or catch a burglar. In this case, the intruder did not steal anything, but only defecated in the middle of the house. Of course, in modern times we also occasionally hear about a drugged out or mentally ill person breaking into a home, only to do something bizarre like raid the refrigerator or go to sleep on the couch.

Instead, he attributes the multiple Fu, placed in all four corners of the house, as causing the would-be thief to hallucinate and become disoriented. It then becomes an automatic bodily response to defecate, as a way to come out from under the spell. After the fact, in the olden days, a Fu could be placed over the muddy footprint left on the ground by the burglar, making it more likely the fleeing person would be found.

Choo notes how common it is for people to burn Fu and mix the ashes into food or liquids to be consumed. But equally acceptable is it to frame a Fu under glass, which implies it will be kept indefinitely.

There are Fu which can appease a deity in charge of the unborn child, especially if the mother’s home is under repair or renovation during the pregnancy. This one reminds me of some of the precautions we take in Feng Shui, with adjustments made for the poor timing of a demolition or remodel. And maybe I can get a little side hustle going doing replications, with permission, of the famous talisman to “enhance one’s attractiveness.”

Getting even more into the spooky realm, there are Fu which can be made of bamboo or straw as figurines (yes: think Voo-doo), which can be used to transfer a person’s upcoming mishaps or misfortune into the “substitute body.” Adding locks of hair or fingernail clippings can assure a DNA connection to the ritual. There are also further embellishments done to groupings of five talisman, to represent the four cardinal directions, plus “center.” The embellishments not only include placement in those literal directions but making Fu with matching colors: east (green), south (red), west (white), north (black) and center (yellow).

In one chapter on consecrating Taoist statues, it appears that items used to do that can be consecrated with the ashes of a talisman meant for consecration ceremonies, so this is either revealing the length one must go to have a truly magical outcome, or it fuels a kind of spiritually-themed obsessive compulsive disorder. I have not figured it out yet.

Through numerous rituals, a statue can be animated or at least draw in a spirit to occupy the statue. The process is called “Opening of Eyes.” As an uninitiated onlooker, it seems like idol worship or pantheism or both. If this is fundamental to Taoism, then I plead ignorance and need to learn more about Taoism. While the statue rituals are really not any stranger than making the paper-fu talisman, the sheer emphasis on the physicality of the statue makes me think there is something else going on. When life is breathed into the statues, they can protect the person who prays or pays homage to them.

I vacillate between thinking this is all very primitive, tribal and superstitious to wondering if the practitioners know something about other dimensions that is still so hidden for the rest of us. I’m fascinated by all of this, in the same way that it is wild how everyone who takes Ayahausca sees elves.

Choo concludes with warnings to not eat or drink the ashes from a Fu in case the paper and ink have toxins in them, which would be the case virtually 100% of the time nowadays. He also shares some “unorthodox” uses of talismans, where the individual making them has chosen to use them to punish people who don’t pay their debts or the ritual for “the Destruction of Mean people,” without giving away the mantra used. The author is justifiably concerned about the karma of releasing that information.

This book, with a few typos and grammatical errors, can be found on Amazon. I would rather read an imperfect book like this, than one with a more professional presentation that was written by an academic and not an actual adept at Fu-making. One reviewer was disappointed that there was not enough instruction to start making your own Fu. I enjoyed reading the cultural and historical perspective he offered.

If I were to respond to that Amazon review, I would encourage the person to read other books on the topic; the only other book I know of which appears exhaustively complete is Benebell Wen’s impressive behemoth, The Tao of Craft, which I also recommend. And if someone truly wants to study and approach this practice with reverence, they should be culling suggestions and instructions from more than one source. Author Ricardo Choo offers his services at the end of the book, to either hire him to make a Fu or study with him remotely.

Author: Kartar Diamond

Company: Feng Shui Solutions ®

From the Book Review Blog Series